Oslo: The Opportunity of Growing Inwards

The Smart Citizen / Vineeta Shetty / June 18, 2019 /

“We are a rich city in a rich country dependent on the oil and gas industry,” is the candid admission of Raymond Johanssen, governing mayor of Oslo. A plumber by original trade, he can convincingly claim to know his city inside and out and he recalls a city which had no running water in several parts in the mid-60s, where factories flushed mercury into the fjord and traffic clogged the highway running alongside it.

Till the current century, the inner city remained a black hole where dads went to work, whereas their boats on the fjords and the hut in the surrounding forests were where Osloborgers took off for recreation. A small and loosely-connected group of urbanists and activists established at the beginning of the 90s were to begin slowly transforming all that. What is now the Oslo Urban Arena, a unique ecosystem uniting urbanists, public planners and private developers, has driven a new era of urban development, starting with the transformation of the former docklands into the Fjord City.

Pioneering urbanist, Erling Fossen, notes that many Western cities such as Amsterdam, are looking back in order to revive the once-glorious DNA hidden in their urban, socio-material fabric. Oslo, having been demolished by fire and decimated by plague, has no DNA, even though the city is more than 1,000 years old. Until it became the capital of an independent Norway is 1814, the city never had more than 10,000 inhabitants. It was only thanks to Norwegian engineers returning from Manchester that the industrial revolution in Oslo kicked off in the second half of the 1800s.

“One of the tragedies of Oslo is that neither the Roman nor the Hapsburg empires bothered to put their mark on the city: there are no priceless remnants of a foreign civilisation,” says Fossen in his book ‘Oslo—Learning to Fly.’ “On the other hand, it also means that the city can be rebuilt from the inside out, since the inner city is not a museum. Other western cities must sprawl in order to handle growth, whereas Oslo can start at its core.”

As an example, Barcode, the new central business district, is being constructed next to the central station, while in other cities, it is often relegated to the distant urban fringe. Since 1984, also, most housing has been constructed in the inner city.

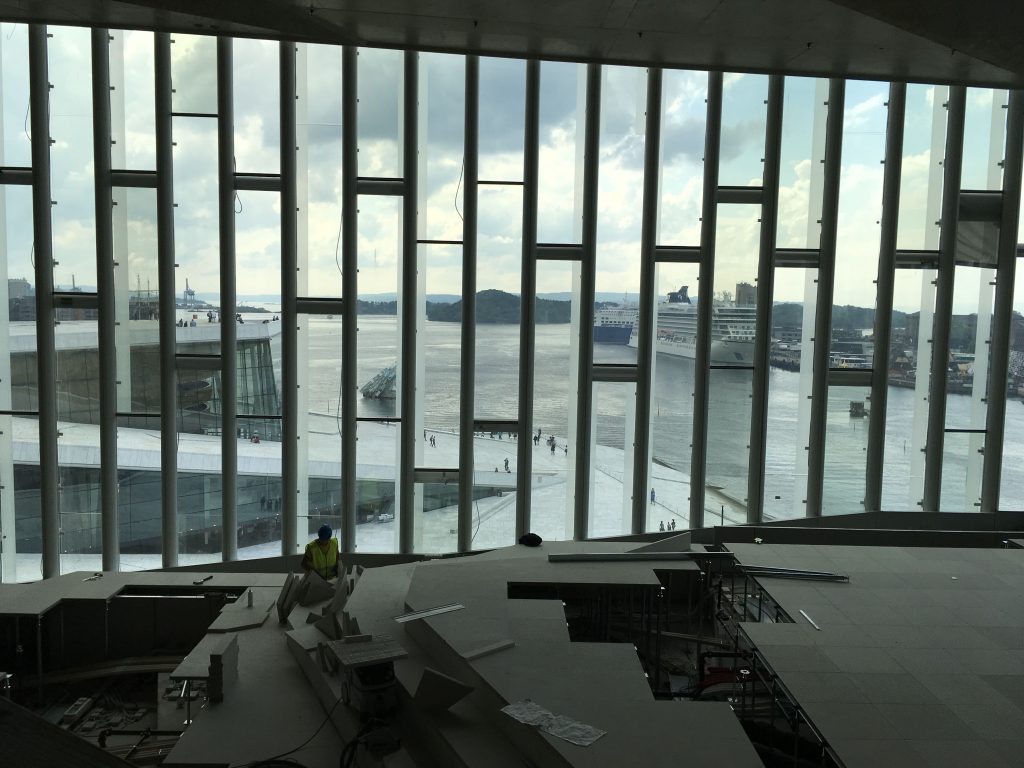

The new Oslo Public Library

To meet the demands of a “compact city” and the needs of the population increase, new housing, workplaces and transport infrastructures will have to be built. At the same time, Norway, as a major fossil fuel exporter, is painfully aware of its commitments under the Paris Agreement on climate change and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. And that means it must act to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50% by 2030, a tall claim for a car-loving country with many remote pockets of population.

While western Norway cities like Stavanger are more affected by the ups and downs in the oil market, Oslo’s market is already fully diversified and employment rate has stabilized around 3%, partly because of the boom in the real estate sector. As Fossen remarks, “it is fair to say that the forest of construction cranes in constructing the DNA of the city.”

Oslo’s own goals are higher than the national goals: it has committed to cutting carbon emissions by 95% by 2030. One of the ground-breaking governance tools it has deployed towards this end is a climate budget. Bridging the internal division in urban administrations between those who think money and those who think emissions, the climate budget is the responsibility of the Deputy Mayor for Finance and monitored in the same way as the financial budget: municipal agencies are policed for carbon emissions and responsibility is allocated for implementing adopted measures.

While Oslo’s transition to e-cars with its controversial subsidies and incentives to well-heeled car-owners is well-documented, less known is the transition to electric cargo and utility transport and shore-based power. The city has taken an international lead, using its purchasing power to create a market and speed up the transition to zero-emission construction vehicles. The world’s first, large electric excavator in Europe was developed by Pon Equipment in Norway and will be used in building sites around Oslo.

In 2009, Oslo partnered with three neighbouring municipalties and six public and private sector institutions to establish FutureBuilt. Created to support climate-friendly urban development in the Oslo region, it aims to complete 50 projects by 2020 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transport, energy and material consumption by a minimum of 50% and to inspire and change practices in both the private and public sector.

The construction sector is the largest consumer of material resources in Norway. Indirect emissions connected to materials and installations used in the building are a significant portion of the building’s total emissions and can be largely affected by the construction sector as a purchaser of construction materials and equipment.

Harald Nikolaisen, the Director General of Statsbygg, the Norwegian Directorate of Public Construction and Property, believes materials are a quicker way to the Paris Goals, rather than operational improvements in energy and transportation. In the construction of the new National Museum for instance, 21% of the GHG reductions came from operational energy, 42% from minimizing transportation to and from the site and 46% from the use of materials to reduce the building’s carbon footprint. This reflects the growing view at apex bodies such as the World Green Building Council that as operating carbon comes down, embodied carbon becomes the main culprit that needs to be arrested to meet the global climate change objectives.

The big offender is the production of concrete, whose emissions are believed to be twice as much as the entire air transport industry. Roughly 90% of the emissions caused by conventional concrete stem from the production of cement, specifically from the crushing of limestone and from fuel used in the chemical process.

FutureBuilt has actively promoted the testing of low-carbon concrete, a material that has a reduced carbon footprint because the binder, amongst other things, contains a lower percentage of cement clinker. Such low-carbon concrete reduces emissions by up to 30% as compared with standard concrete.

The new Munch Museum looms over the skyline of Fjord City

The new Munch Museum and the Oslo Public Library, which are set to open to the public at the end of the year, are examples of low-emission construction. Their iconic location flanking the new Opera House on former wasteland on the waterfront does not diminish their high environmental ambition.

Oslo Public Library, planned as a living room for the city according to its architects, will be the most high-profile example of reductions of 50% over the original building occupied, by the use of low-emission concrete. Passive energy of concrete is also captured by putting cooling water pipes within.

However, project managers AF Advansia did face a few challenges mixing fly ash into the concrete to bring down its carbon content. Hybrid concrete is temperature-sensitive, something that affects the progress of construction. They also discovered that bubbles mar the appearance of the visible parts of the building. They opted to reduce the fly ash content in the exterior and mix it in in less visible parts of the building, thus helping them achieve the carbon target.

District heating was already in use while the building was coming up, so it was used instead of diesel and gas, an unexpected environmental boon.

Contentious as the 12-storey Munch Museum designed by estudio Herreros has been among urbanists and citizens, it also follows FutureBuilt’s criteria of atleast a 50% cut in GHG emissions. Among the considerations here were an external skin with good insulation; high heat recovery and high use of recycled air; energy efficient lighting and proximity to Norway’s most important public hub, the Oslo rail station.

According to the FutureBuilt Programme Director, Stein Stoknes, refining and using solutions such as low carbon concrete depends on the production and demand sides cooperating well. The goal is to mobilise leading, high-profile real estate developers to actively use their market power and demand the concrete solutions of the future.

Procurement and partnership have been key to Oslo’s success in reducing its carbon footprint. Governing Mayor Johannsen sends a strong signal to the business community: if you want to operate here, you must align with the city’s commitment to cut carbon emissions.